Dir: Katell Quillevere

Katell Quillevere's third feature, adapted from a novel by Maylis de Kerangal, takes organ transplants as its subject, following a single procedure (a heart transplant) from both sides; that of the family of the donor and of the the recipient and her family. This is where my history comes into play: I have received two liver transplants (25 years ago, within 10 days of each other), so I have experienced this journey from one side and have often imagined what it must have been like from the other. For other viewers these events may be more abstract, but for me Heal the Living was deeply and devastatingly personal.

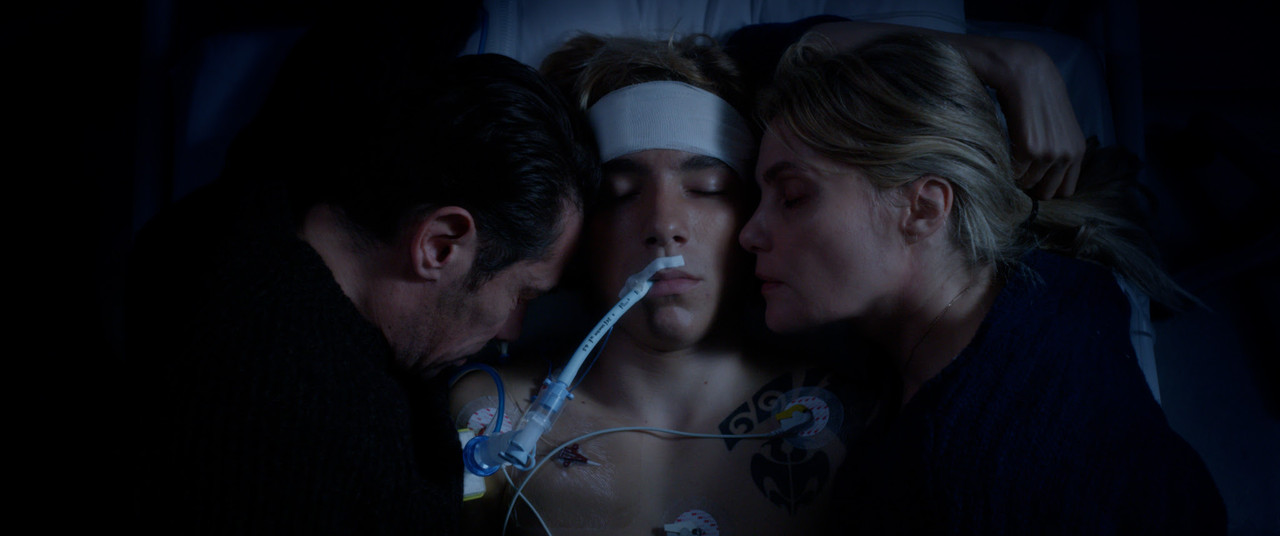

The donor is Simon (Gabin Verdet), brain dead after a car accident, and we are privy to the whole process as a young doctor (Tahar Rahim) sensitively introduces the prospect of donation to the devastated parents (Emmanuelle Seigner and Kool Shen). From the other side we see Claire (Anne Dorval) slowing down her life as she is placed on the transplant list and also trying to moderate the impact on her late teenage children (Finnegan Oldfield, Theo Cholbi). Quillevere divides the two parts quite decisively, only introducing Claire after about an hour, but also allowing time for each side of the story to develop independently before drawing them together.

The two parts of the film have similar form, but slightly different styles. In each section Quillevere allows for a few digressions, for instance following Monia Chokri's nurse for a little while and showing Claire reconnecting with a former lover (Alice Tagliolini), but the first hour has a more dreamlike feel, while the second half largely abandons those touches for something much closer to documentary style. For me, this seems to suggest the sense of dislocation that the extreme grief of Simon's parents must be causing for them spilling over into the film. This is acutely felt in a brief flashback to the first time Simon and his girlfriend kiss, a sweet scene which trades on Quillevere's mastery of coming of age cinema (her first film, Love Like Poison, is one of the 21st century's great entries in that genre). After sweeping you up briefly in this romantic moment, Quillevere immediately cuts to an ashen Seigner and Kool Shen, driving back from the hospital. The flashback is not a memory but either a parent's imagining of a moment in their son's life, now brutally cut short, or a memory of how he told that story. We never know which, but the question alone is affecting.

There are more beautiful directorial flourishes in the film's first part; the road becoming the sea as Simon's friend falls asleep at the wheel, causing the crash; images of Simon surfing, as if being sucked under into another world. These are not only striking in themselves, but in the contrast with the second half. Once Claire is introduced everything is matter of fact. Quillevere becomes more an observer, first of the relationship between Claire and her sons, then of the transplant procedure itself. Both operations, the harvesting and the transplant, are handled sensitively and with a matter of fact eye for procedure, but with enough restraint that the film always feels honestly sad, rather than sentimental.

This is delicate material, but Quillevere and her outstanding cast handle it beautifully. Tahar Rahim strikes a perfect balance between playing his character's desire to get consent for Simon's organs to be used and his determination to handle it with maximum sensitivity, while Seigner and Kool Shen, with relatively limited screentime, sketch believable studies of grief. In the second half, Anne Dorval finds a lot of moments that struck home for me, especially in the sequences after she gets the call to hospital; the nerves, the preparation, the goodbyes, all these things ring true and brought back raw images from 25 years ago. Even the small parts are expertly cast and played, with especially fine work from Bouli Lanners and Dominique Blanc.

Quillevere's balance between realism and poetic touches is exceptional throughout, but the moment that Rahim pauses the harvesting operation to say a few last words to Simon from his family is where it hits hardest. Devastatingly touching without ever feeling sugary or false, it's a moment that shows the film in miniature.

After the blip I felt Suzanne represented after Love Like Poison, this is a dazzling piece of work from Quillevere. Heal the Living is beautifully cast and acted, expertly directed and well made in every technical respect, but for me it was so much more than that. Transplant isn't a subject often addressed in cinema, the last time I remember seeing it covered was in a very different context in Never Let Me Go, but Heal the Living has none of the abstraction and distance that Mark Romanek's film did. Instead this film lives in some of the most emotionally fraught moments of people's lives and rings true at every turn. I can't say whether other audiences will feel this film as viscerally as I did, but even if they don't, it remains essential viewing.

★★★★★

The donor is Simon (Gabin Verdet), brain dead after a car accident, and we are privy to the whole process as a young doctor (Tahar Rahim) sensitively introduces the prospect of donation to the devastated parents (Emmanuelle Seigner and Kool Shen). From the other side we see Claire (Anne Dorval) slowing down her life as she is placed on the transplant list and also trying to moderate the impact on her late teenage children (Finnegan Oldfield, Theo Cholbi). Quillevere divides the two parts quite decisively, only introducing Claire after about an hour, but also allowing time for each side of the story to develop independently before drawing them together.

The two parts of the film have similar form, but slightly different styles. In each section Quillevere allows for a few digressions, for instance following Monia Chokri's nurse for a little while and showing Claire reconnecting with a former lover (Alice Tagliolini), but the first hour has a more dreamlike feel, while the second half largely abandons those touches for something much closer to documentary style. For me, this seems to suggest the sense of dislocation that the extreme grief of Simon's parents must be causing for them spilling over into the film. This is acutely felt in a brief flashback to the first time Simon and his girlfriend kiss, a sweet scene which trades on Quillevere's mastery of coming of age cinema (her first film, Love Like Poison, is one of the 21st century's great entries in that genre). After sweeping you up briefly in this romantic moment, Quillevere immediately cuts to an ashen Seigner and Kool Shen, driving back from the hospital. The flashback is not a memory but either a parent's imagining of a moment in their son's life, now brutally cut short, or a memory of how he told that story. We never know which, but the question alone is affecting.

There are more beautiful directorial flourishes in the film's first part; the road becoming the sea as Simon's friend falls asleep at the wheel, causing the crash; images of Simon surfing, as if being sucked under into another world. These are not only striking in themselves, but in the contrast with the second half. Once Claire is introduced everything is matter of fact. Quillevere becomes more an observer, first of the relationship between Claire and her sons, then of the transplant procedure itself. Both operations, the harvesting and the transplant, are handled sensitively and with a matter of fact eye for procedure, but with enough restraint that the film always feels honestly sad, rather than sentimental.

This is delicate material, but Quillevere and her outstanding cast handle it beautifully. Tahar Rahim strikes a perfect balance between playing his character's desire to get consent for Simon's organs to be used and his determination to handle it with maximum sensitivity, while Seigner and Kool Shen, with relatively limited screentime, sketch believable studies of grief. In the second half, Anne Dorval finds a lot of moments that struck home for me, especially in the sequences after she gets the call to hospital; the nerves, the preparation, the goodbyes, all these things ring true and brought back raw images from 25 years ago. Even the small parts are expertly cast and played, with especially fine work from Bouli Lanners and Dominique Blanc.

After the blip I felt Suzanne represented after Love Like Poison, this is a dazzling piece of work from Quillevere. Heal the Living is beautifully cast and acted, expertly directed and well made in every technical respect, but for me it was so much more than that. Transplant isn't a subject often addressed in cinema, the last time I remember seeing it covered was in a very different context in Never Let Me Go, but Heal the Living has none of the abstraction and distance that Mark Romanek's film did. Instead this film lives in some of the most emotionally fraught moments of people's lives and rings true at every turn. I can't say whether other audiences will feel this film as viscerally as I did, but even if they don't, it remains essential viewing.

★★★★★

No comments:

Post a Comment