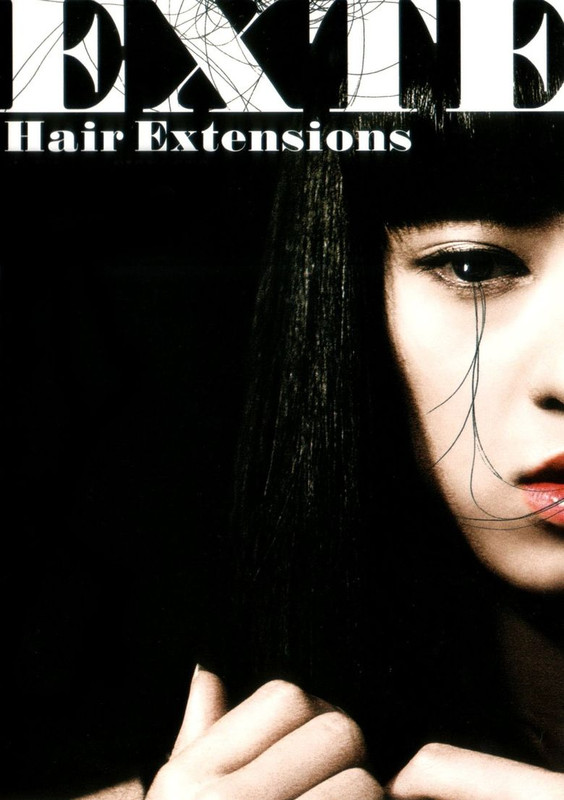

Exte [15]

Dir: Sion Sono

Sion Sono has fast become not just one of my favourite Japanese filmmakers but one of my favourite directors full stop. I’ve seldom encountered any filmmaker with such a mad imagination and such a distinctive touch, so it seemed appropriate to begin and end this month long series of Japanese films with his work. 2007′s Exte, while not exactly a spoof, does seem to be a good-natured nudge at the proliferation of Japanese films which, in the wake of Ringu, used the imagery of the long haired ghost girl. Here Sono takes that image to its illogical conclusion, spinning a tale of a hair fetishist morgue attendant, who discovers a corpse whose hair is still growing at an exponential rate, steals the body and sells the hair as extensions – possessed extensions which kill the women who wear them. Yes, you read that correctly.

Okay, so far, so batshit crazy sounding, and while Exte certainly delivers the goods on that front, Sono isn’t content merely to make a slice of blackly comic weirdness. One of the recurring themes of Sono’s films seems to be parental abuse, and the main character here is Yuko (Chiaki Kuriyama), who ends up having to take her young niece in because her Mother (Yuko’s half sister) has been beating her. It is deeply strange and out of place feeling when this story element first rears its head in the film, but Sono uses it to effectively cut through the fact that the rest of the film is so outlandish, and actually gets a couple of scenes with some emotional resonance (in, I remind you, a film about possessed hair extensions). Of course the abuse storyline also leads to one of the film’s most jaw-dropping scenes, which actually made me say ‘what the fuck?’ out loud at my TV, when the hair extensions appear to become vengeful.

Sono’s imagery is memorably disgusting, despite barely a drop of blood being spilled. The hair becomes this horrific entity with a life of its own, and when it is squeezing into or coming out of places it has no business being the film really makes the skin crawl. There are also blackly comic moments in the imagery, none more so than the hilarious last image of the morgue attendant. There are probably a lot of ways to take a sequence like a girl seemingly vomiting endless streams of hair from all over her body (is Sono commenting on the overuse of that image in Japanese cinema?), but I prefer to look at it simply as Sono having fun going completely over the top.

Helpfully for the film, some solid performances just about nail it to the ground; Kuriyama (best known in the West for Battle Royale and Kill Bill) is seen in a very different context than I’ve seen her before, and she’s charming as the film’s trainee hairdresser heroine, while Ren Osugi gives off severe creepy vibes as the morgue attendant Yamazaki.

Exte is deeply odd, but, as with most of Sono’s work, there is something hypnotic about its eccentricity. In fact, this might be the perfect gateway drug to Sono’s work: it plays with images that audiences know, is relentlessly entertaining, hits many of the director’s favoured themes, and, unlike his masterpiece Love Exposure, doesn’t take 4 hours to watch.

★★★★

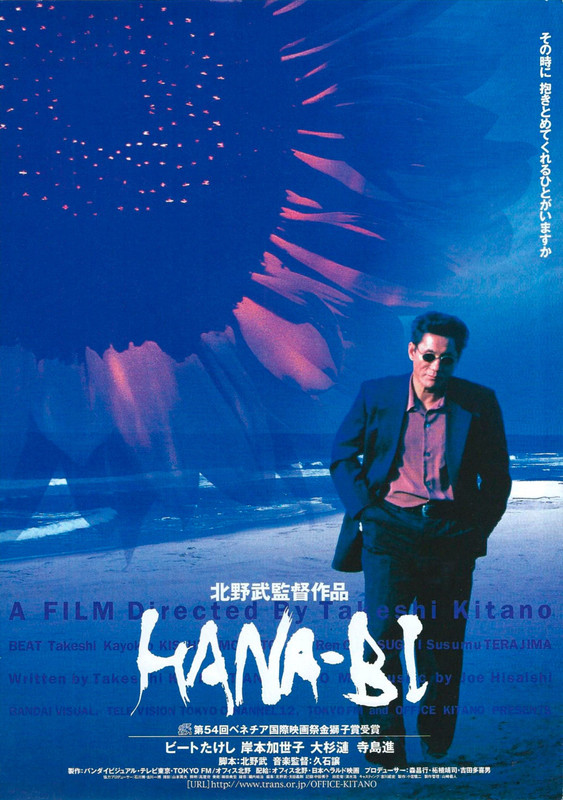

Hana-Bi [18]

Dir: Takeshi Kitano

Takeshi Kitano is a filmmaker I’ve previously known largely by reputation, the only other film I’ve seen of his being his Zatoichi remake, which I wasn’t overly fond of, as I recall. He’s certainly an interesting figure though; a TV presenter and comedian who broke into serious filmmaking and is now feted by film fans the world over. It’s hard to picture the same happening here – imagine Ant and Dec becoming respected auteurs, while still presenting their shows – but I think I can see a bit of Kitano the comedian sneaking in to Hana-Bi, despite its very downbeat story.

Kitano plays Nishi; an ex cop who leaves the force after his partner Horibe (Ren Osugi) is seriously wounded while Nishi is visiting his dying wife (Kayoko Kishimoto) in the hospital. After leaving the force, Nishi, indebted to the Yakuza for his wife’s treatment, robs a bank and takes his wife on a last holiday. As this is happening, the paraplegic Horibe finds some solace in painting surreal works of art.

I can see, watching Hana-Bi, why people love Kitano’s work. There’s a real sense of craft and of personal vision here. Kitano is writer, director, editor and lead actor, so the film really does come from him. For me this is both good and bad. Kitano’s camerawork and editing are often outstanding; the intensely composed nature of his shots, the stillness of his camera and the measured pace of most of the scenes is occasionally expertly and thrillingly broken by jarring cuts to violent confrontation, and from violence back to great stillness. The thing is, as well as these things work visually, at times they don’t serve the story or the film’s overall tone that well.

The two major storylines are both about men trying to come to terms with loss. For Nishi the past loss of his daughter (which echoes movingly in the film’s last scene, through a moment featuring Kitano’s own daughter) and the impending loss of his wife, and for Horibe the loss of the use of his legs, and of his own wife and child, who apparently walk out on him. These storylines sit awkwardly against the sudden violence of the Yakuza storyline, which sometimes seems to have teleported in from another film. There are other little awkward things; the brief interludes at a junkyard where Nishi buys a car are a good example, I never saw why the film needed to return there after that transaction was done. From what I understand, Kitano’s films prior to Hana-Bi lean more heavily on violence and on Yakuza storylines, to me their inclusion here feels almost like a filmmaker who isn’t entirely sure whether an established audience will follow him in a new direction.

The weaknesses, however, don’t keep Hana-Bi from being very engaging. The performances all match the quiet tone of the bulk of the film, and Kitano gets real emotion out of some resolutely undemonstrative work from his cast. The story can be very downbeat, but there is a vein of humour that lends the film a warmth and keeps it from being depressing, it’s a shame that, however well it works technically, the film’s violence jars the tone too much for me. That said, without knowing more about his work, the problems here would seem to peg Hana-Bi as a transitional film, and one that makes me more interested in seeing what Kitano did either side of it.

★★★

No comments:

Post a Comment